Metacognition and Embodied Learning

Metacognition

Metacognition, a term that was

first defined by John H. Flavell in 1979, is

basically thinking about thinking. With metacognition, we become aware of our

own learning experiences and the activities we involve ourselves in our paths

toward personal and professional growth. We are better able to understand

ourselves in the whole process of learning and can develop skills to think

about, connect with, and evaluate our learning and interactions each day. According

to Flavell, metacognitive knowledge is

“knowledge about one’s own cognitive processes or products.

Metacognition has been identified as an essential skill for learner success. It

allows students to drive their learning, build student agency, and

foster a growth mindset in learning.

In order to develop metacognitive skills and

habits in the classroom

•

First, students must have the opportunity to practice and so must be

placed in situations that require metacognition. They should know the meaning

and importance of metacognition, and the development of the capacity for it

must be an explicit goal for both teacher and student. This goal must have a credible and enduring presence in the established

curriculum and in assessments.

•

Second - connecting to Vygotsky's teachings -metacognition can and should

be modelled. When a teacher "thinks aloud," particularly during

problem solving, his or her verbalizations can be a powerful source of

cognitive processing that can be internalized by students. This has been called

cognitive modeling, or "making thinking audible."

•

Third, just as teachers should model metacognition, social interaction

among students should be used to cultivate their metacognitive capacity. If

students are encouraged and guided to think critically together, then their

spoken reasoning will ideally make their cognitive tools available to one

another.

In metacognitive learning a key challenge for teachers is being able to recognise how well their students understand their own learning processes.

References

Flavell, John H. 1979. “Metacognition and Cognitive

Monitoring: A New Area of Cognitive-Developmental Inquiry.” American

Psychologist 34 (10): 906–911.

Descartes was the first to

formulate the mind–body problem in the form in which it exists today. Dualism is the view that

the mind and body both exist as

separate entities. Descartes / Cartesian dualism

argues that there is a two-way interaction between mental and physical

substances. Descartes argued that

the mind interacts

with the body at the pineal

gland. Descartes described on one

side the body as a material “machine” containing organs and following the laws

of nature. On the other side, he described the mind

as non-material and independent of the laws of nature. The interaction between body

and mind would be enabled by the pineal gland, the “seat of the soul.”

Rationalism has strongly influenced cognitive sciences in the

20th century. Fodor et al. (1974) described the

mind as a set of computational operations subdivided in modules that are

defined in terms of their function. Originally, Fodor saw no connection between

a module and the reference world outside. He separated the mind from the body in the

manner of Cartesian philosophy. This was the core

idea behind the view that, when acquiring knowledge, we sit quietly and concentrate on

our “mental” task(s). With the advent of

neuroscience, Rationalism has been greatly challenged. Theories of embodied

cognition suggest that the mind is not an abstract and isolated entity. Rather the mind is integrated into the

body’s sensorimotor systems. The embodied view

of cognition is grounded in sensory and motor experiences (Engel et al., 2013; Mahon and Hickok,

2016).

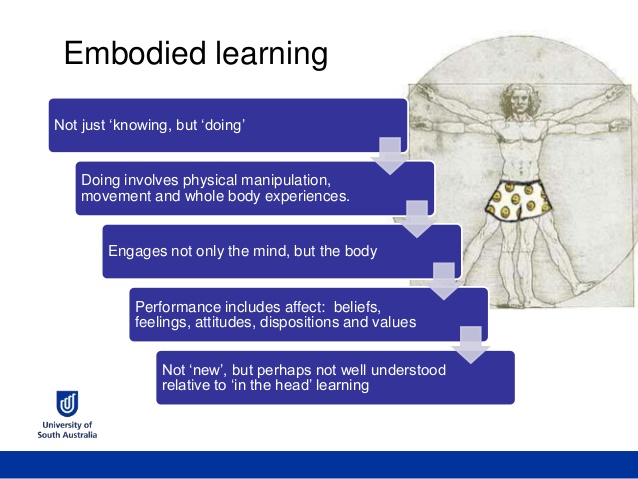

Embodied learning refers to pedagogical approaches that focus on the

non-mental factors involved in learning, and that signal the importance of the body and feelings. Embodied Learning constitutes a

contemporary pedagogical

theory of learning, which emphasizes

the use of the body in the educational practice and the student-teacher interaction both

inside and outside the classroom and in digital environments as well.

Embodied learning is;

- · Experiential

- · Practical

- · Hands on

- · Physical

- · Activates cognitive, affective and somatic dimensions

In accordance with the constructivist principles, the body is used

both inside and outside classroom for experiential learning and is not treated

as a place of learning. The principles of Embodied Learning provide answers to

questions related to the ways knowledge is constructed by students as they

leave behind them the academic model of perceiving knowledge and treat each

student as a whole, while they view everyone’s body as a tool for knowledge

construction and as a knowledge carrier.

References:

Asher, J. J. (1969). Total physical

response technique of learning. J. Spec. Educ. 3, 253–262. doi: 10.1177/002246696900300304

Fodor, J., Bever, T. G., and

Garrett, M. F. (1974). “The psychology of language,” in An Introduction to Psycholinguistics and Generative Grammar, eds J. A. Fodor,

T. G. Bever, and M. F. Garrett (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill).

Engel, A. K., Maye, A., Kurthen,

M., and König, P. (2013). Where’s the action? The pragmatic turn in cognitive

science. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 202–209.

doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.03.006

Mahon, B. Z., and Hickok, G. (2016).

Arguments about the nature of concepts: symbols, embodiment, and beyond. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 23, 941–958. doi: 10.3758/s13423-016-1045-2

Comments

Post a Comment